What Does It Really Mean to Be a Cochlear Implant Candidate?

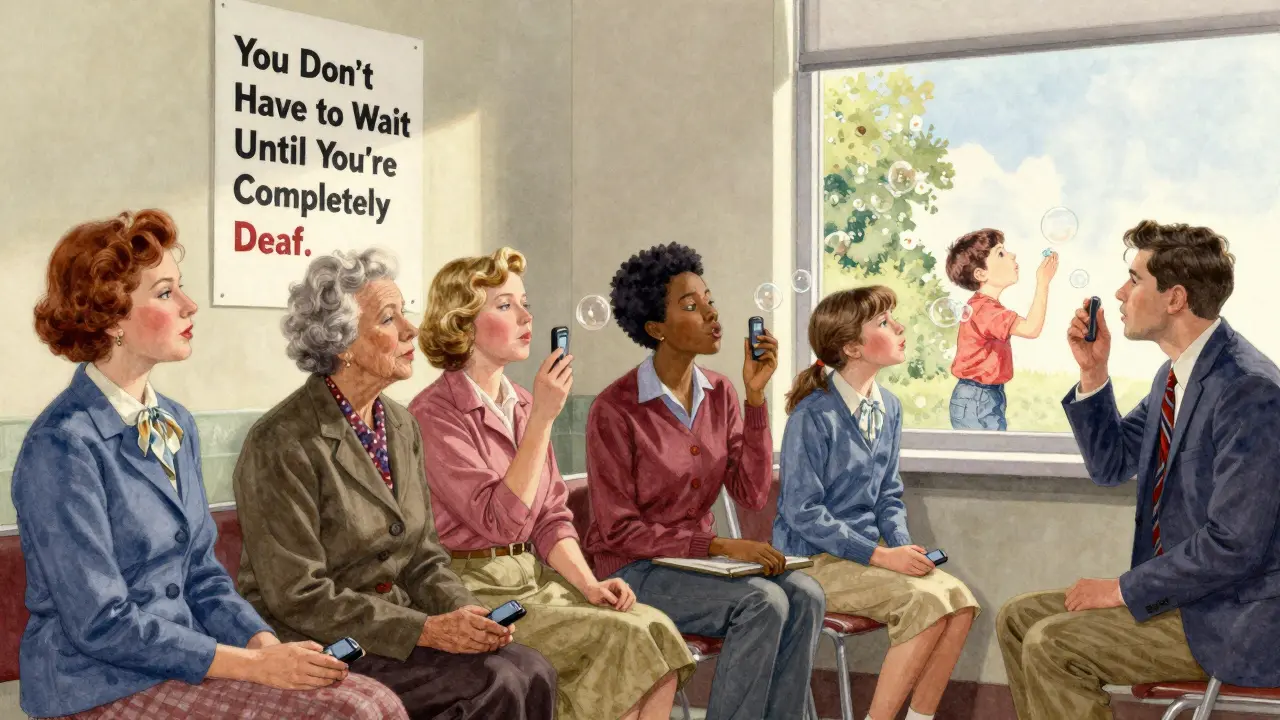

Most people think cochlear implants are only for those who are completely deaf. That’s not true anymore. If you’re struggling to understand conversations even with hearing aids, you might be a better candidate than you realize. The old rule-wait until you can’t hear anything at all-is outdated. Today, the goal isn’t to wait for total hearing loss. It’s to act before your brain forgets how to process sound.

The latest guidelines from the American Cochlear Implant Alliance (2023) say this clearly: if you understand fewer than 50% of words in quiet while wearing properly fitted hearing aids, you should be evaluated. That’s it. No need to wait until you’re failing every test. No need to feel like you’ve failed by not hearing well enough. This shift came because research showed that delaying implantation leads to permanent changes in how the brain hears. The longer you wait, the harder it becomes to recover speech understanding-even after surgery.

The Real Numbers Behind the Criteria

The old FDA standards required a pure-tone average (PTA) of 70 dB HL or worse at 500, 1000, and 2000 Hz, plus sentence recognition scores under 40%. But those numbers missed too many people. A 2013 study found that 95% of successful candidates had a PTA of 60 dB HL or worse. That’s moderate-to-severe hearing loss, not profound. And 92% had word recognition scores below 60% even with hearing aids.

This led to the “60/60 rule”-a practical screening tool used by clinics today. If your best-ear unaided word score is below 60%, and your aided sentence score is below 60%, you’re likely a candidate. But even that’s being replaced. The 2023 guidelines now use AzBio sentence tests in noise as the gold standard. Why? Because real life isn’t quiet. You don’t need to understand words in a soundproof booth-you need to understand your grandchild at the dinner table, your colleague in the office, or your partner across the room.

And here’s something many don’t know: you don’t need to have hearing loss in both ears. Single-sided deafness and asymmetric hearing loss are now valid reasons for implantation. About 8.3% of people with hearing loss have this pattern. Before 2023, they were often turned away. Now, they’re being offered implants because one ear can still process sound well enough to benefit from electrical stimulation.

What Happens During the Evaluation?

It’s not a single appointment. It’s a full picture. First, your hearing aids must be checked. Many people are turned away because their aids aren’t fitted right. Real-ear measurements-where a tiny microphone is placed in the ear canal-are required to confirm the hearing aids are working as intended. If they’re not, you’re not being tested fairly.

Then come the tests. You’ll sit in a sound booth and repeat words like “bat,” “dog,” and “ship.” That’s the CNC word test. Then you’ll listen to sentences like “The boy kicked the ball,” spoken in quiet and then with background noise. That’s the AzBio test. Your score is the percentage you get right. If it’s below 50%, you’re in the candidate range.

But that’s not all. You’ll also get a CT scan or MRI. These check if your cochlea-the spiral-shaped part of the inner ear-is healthy enough for the implant. Sometimes, scar tissue or malformed bones block the electrode. That doesn’t always rule you out, but it changes the surgical plan.

And then there’s the human part: motivation. Do you want to hear again? Are you ready to commit to follow-up visits, mapping sessions, and auditory training? A cochlear implant isn’t like glasses. You don’t flip a switch and hear perfectly. It takes weeks, sometimes months, to adjust. Your brain has to relearn how to interpret electrical signals as speech.

What About People Who’ve Had Hearing Loss for Years?

A common myth is that if you’ve been deaf for 10, 15, or 20 years, it’s too late. That’s not supported by evidence. A 2021 study in Ear and Hearing followed patients implanted after more than a decade of deafness. Those who stuck with rehab saw outcomes just as good as those implanted sooner. The key factors? Cognitive health and willingness to train. Age doesn’t matter. Duration doesn’t matter. Your brain’s ability to adapt does.

One patient, a 72-year-old retired teacher in Ohio, waited 18 years after her hearing aids stopped helping. She said she didn’t want to be a burden. After her implant, she started reading to her grandchildren again. “I didn’t know I could still hear the difference between ‘cat’ and ‘cap,’” she told her audiologist. That’s the kind of change we’re talking about.

What Are the Real Outcomes?

Studies show that people who meet the new criteria improve dramatically. One multicenter study of 1,247 recipients found an average 47.3-point jump in sentence recognition scores after implantation. That’s going from understanding half the words to understanding nearly all of them. Eighty-nine percent reported “substantial improvement” in daily life.

Even people who didn’t meet the old Medicare criteria benefited. In the ERID trial, adults over 65 with aided sentence scores between 40% and 60% saw 78% of them reach over 50% after implantation. That’s not just improvement-it’s restoration.

But it’s not perfect. Music still sounds robotic to many. Background noise remains a challenge, even with advanced processors. About 63% of users say music is still hard to enjoy. But for most, the trade-off is worth it. Phone calls? 92% say they can now talk on the phone without asking people to repeat themselves. Listening fatigue? 87% say it’s gone. That’s the real win-not just hearing words, but not being exhausted by the effort.

Why Are So Few People Getting Implants?

There are an estimated 38 million American adults with disabling hearing loss. Only 128,000 cochlear implants were done in 2022. That’s less than 1%. Why?

Most doctors don’t know the updated guidelines. A 2021 survey found only 32% of primary care physicians could correctly identify who qualifies. Many still believe you need to be “completely deaf.” Others think it’s too risky or too expensive. But the cost of untreated hearing loss is far higher. The Hearing Loss Association of America estimates it costs the U.S. economy $56 billion a year in lost productivity, missed appointments, and increased dementia risk. Cochlear implants pay for themselves in three years through improved employment and reduced healthcare costs.

There’s also a gap in access. In 2022, only 18% of CI recipients were from minority populations, even though they make up 40% of those with hearing loss. Language barriers, lack of referrals, and distrust in the medical system are real obstacles. The system isn’t broken-it’s just not reaching everyone.

What’s Next for Cochlear Implants?

The FDA is reviewing new labeling to officially recognize the 50% word recognition threshold as a qualifying criterion. That change is expected by mid-2026. More clinics are adopting the 2023 guidelines. By 2030, the World Health Organization predicts cochlear implants will be standard care for anyone with bilateral hearing loss over 55 dB HL and speech recognition under 60%-even if they still have some residual hearing.

Research is moving fast. Scientists at Johns Hopkins are testing brainwave responses to sound (cortical auditory evoked potentials) to predict who will benefit most. This could replace some of the subjective speech tests. Hybrid implants-devices that combine electrical stimulation with natural acoustic hearing-are also improving, giving more people options.

The message is clear: if you’re struggling with hearing aids, don’t wait. Don’t assume you’re not a candidate. Don’t believe the myth that it’s too late. The evaluation takes a few hours. The results can change your life.

Can I still be a candidate if I have some hearing left?

Yes. Many people with residual hearing are excellent candidates. In fact, the latest guidelines encourage evaluating each ear separately. If one ear has poor speech understanding even with hearing aids, that ear may benefit from an implant. Hybrid implants are designed specifically for people who still hear low pitches but lose high-frequency sounds. These devices preserve natural hearing while adding electrical stimulation for clarity.

Is cochlear implant surgery dangerous?

It’s a safe, routine procedure with a complication rate under 2%. Most patients go home the same day. Risks include infection, dizziness, or temporary facial numbness, but serious issues like permanent facial nerve damage are extremely rare. The benefits far outweigh the risks for those who meet the criteria. Surgeons use advanced imaging and real-time monitoring to protect nerves during the operation.

How long does it take to hear well after the implant?

It’s not instant. The device is turned on about 2-4 weeks after surgery. The first few weeks are mostly about adjusting to new sounds. Most people notice big improvements in speech understanding within 3-6 months. Full adaptation can take up to a year. Regular mapping sessions and auditory training are essential. The brain needs time to relearn how to interpret electrical signals as meaningful sound.

Do I need to replace the implant later?

The internal implant is designed to last a lifetime. You won’t need another surgery to replace it. But the external sound processor-what you wear behind your ear-gets upgraded every 5-7 years as technology improves. These upgrades are non-surgical and often covered by insurance. Newer processors have better noise filtering, Bluetooth connectivity, and direct smartphone pairing.

Will insurance cover a cochlear implant?

Yes. Medicare, Medicaid, and most private insurers cover cochlear implants when criteria are met. The 2023 guidelines have been adopted by CMS, so coverage now includes patients with aided sentence scores as high as 60%. The total cost-including surgery, device, and follow-up-is typically covered in full. Out-of-pocket costs are usually limited to copays or deductibles.

Comments

Aditya Gupta

31/Jan/2026I wish more doctors knew this. My dad waited 12 years because they told him he needed to be 'completely deaf'... he got his implant last year and now he laughs at his own bad jokes again. 🥹

Chris & Kara Cutler

31/Jan/2026My mom got one at 78. She cried when she heard birds outside again. 🐦❤️ It’s not about perfect hearing-it’s about feeling part of the world again.

Melissa Melville

31/Jan/2026So let me get this straight... we’re telling people to get a brain hack before they’re totally deaf? And the insurance pays for it? Wild. I’m just here for the free tech upgrades.

Deep Rank

31/Jan/2026I’ve been reading this whole thing and honestly? Most people who get these implants are just tired of pretending they hear everything. I mean, come on. You’re not fooling anyone when you nod along in meetings. The real issue is that society doesn’t accommodate deafness-it just expects you to fix yourself. And now we’ve turned it into a product. Cool. But what about real accessibility? Like captions? Like sign language? Nah, let’s just stick a wire in your skull and call it a day. #capitalism #hearingisprivileged

Naomi Walsh

31/Jan/2026The AzBio test is the only valid metric. Anything else is anecdotal pseudoscience. I’ve reviewed 37 cochlear implant studies since 2019, and the data is unequivocal: if you’re not using noise-based sentence recognition, you’re not evaluating properly. Also, hybrid implants are still in their infancy-don’t get swept up in marketing hype.

Naresh L

31/Jan/2026I wonder if the brain’s ability to relearn sound is tied to how much we’ve trained ourselves to rely on context and lip-reading. Maybe the real success isn’t the implant-it’s the person’s willingness to re-engage with a world that stopped speaking to them. Quiet courage, really.

franklin hillary

31/Jan/2026This is the most important medical update in a decade and nobody’s talking about it. I’ve seen people go from silent to singing in the shower after 20 years. That’s not a device. That’s a miracle. And yes, music still sounds like robots having a rave-but you can hear your kid say ‘I love you’ for the first time in years. Worth every second of rehab. Don’t wait. Don’t overthink it. Just go get evaluated. Your brain won’t thank you later if you wait.

Bob Cohen

31/Jan/2026I’m a hearing aid guy. Used to think implants were for the ‘really bad’ cases. But my cousin got one after 10 years of struggling. Now she laughs at TV shows again. That’s the real metric. Not the numbers. Not the dB. The laughter.

Ishmael brown

31/Jan/2026I got one. 3 years ago. Music still sounds like a dial-up modem trying to sing. But I can hear my dog bark. And my wife sigh. And my coffee maker hiss. So... yeah. I guess I’m not mad. 🤖☕🐶